in RBL by Joshua Schwartz

Two new publications

Lieve M. Teugels.

“From the Lion to the Snake, from the Wolf to the Bear. Rescue and Punishment in Classical Fables and Rabbinic Meshalim”, in Overcoming Dichotomies: Parables, Fables, and Similes in the Graeco-Roman World, ed. J. Pater, A. Oegema, M. Stoutjesdijk (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2022), 217-236. Find here a prepublication version.

― . “Keepers of the Vineyard and the Fence around the Torah: The Vineyard Metaphor in Rabbinic Literature,” JSJ 53/2 (2022) 377-404. doi:10.1163/15700631-bja10045. Find here a pre-publication version.

Lieve Teugels als docent aan het Schechter Instituut

Van 23 tot 27 mei jl. heeft Lieve Teugels als gastdocent colleges gegeven aan het Schechter Instituut in Jeruzalem in het kader van de Erasmus+ samenwerking tussen de PThU en dat instituut. Ze heeft daar een aantal colleges gegeven op het gebied van de midrasj, de vroeg-Joodse uitleg van de Hebreeuwse Bijbel.

Het bezoek van Teugels aan het Schechter Instituut volgde onmiddellijk op het verblijf van twee gastdocenten van het Schechter aan de PThU een week eerder.

Op maandag heeft zij twee colleges gegeven. Het eerste betrof een cursus “Jewish Thought” waarin op het moment van Teugels’ verblijf het onderwerp “Eschatologie” aan de orde was. In dit kader heeft zij met de studenten rabbijnse teksten gelezen over de rol van de profeet Elia aan het einde van de tijden, en met name zijn, niet door alle rabbijnen geaccepteerde, bijdrage aan de wederopstanding van de doden. Vergelijkingen met de voorstellingen van Elia in het Nieuwe Testament kwamen uiteraard ook langs.

’s Middags heeft zij gedoceerd in de cursus “Introduction to Midrash.” Haar gastvrouw, dr. Gila Vachman had haar gevraagd om rabbijns-Joodse parabels te bespreken en deze te vergelijken met parabels uit het Nieuwe Testament. Onder andere de parabel van de talenten, de werkers in de wijngaard, en de metafoor van de oude wijn in nieuwe zakken passeerden de revue. Al deze motieven komen op gelijkaardige toch ook verschillende manieren terug in beide literaire tradities, wat interessante discussies opleverde. Voor de studie van de teksten uit het Nieuwe Testament werd de Hebreeuwse vertaling van Franz Delitsch (Leipzig 1883) gebruikt, een mooie vertaling in de stijl van het Bijbelse Hebreeuws. In het Hebreeuws gaan de parabels van Jezus meteen veel meer lijken op hun rabbijnse tegenhangers.

Op woensdagavond heet Gila Vachman Lieve meegenomen naar Tel Aviv waar het Schechter een lokale afdeling heeft in de mooie wijk Neve Tsedek, toepasselijk Neve Schechter genaamd. Die avond stond een studiegroep over het tractaat Sota uit de Babylonische Talmoed op het programma, waaraan Teugels heeft bijgedragen. Daarna volgde nog een boeiende lezing door Abigael Manekin-Bamberger van de Hebreeuwse Universiteit over oude Joodse magie, met name bekend uit Aramese toverschalen. Op shabbat is Lieve teruggekeerd naar de mooie synagoge van het Neve Schechter voor de shabbat ochtenddienst. De Tora werd gelezen uit een zeer fraaie rechtopstaande Tora-rol, en zij had de eer om opgeroepen te worden voor een alia (zegening voor de toralezing) waardoor ze rol van dichtbij kon bewonderen.

Als extraatje heeft Doron Bar, president van het Schechter en een oude bekende van de PThU, Lieve en haar dochter Ester, die momenteel in Tel Aviv studeert, op donderdagochtend meegenomen op een rondleiding over de tempelberg. Momenteel is deze omstreden plek veel in het nieuws. Die ochtend hebben wij echter vrij kunnen rondlopen en de mooie staaltjes van Arabische bouwkunst mogen bewonderen, met de deskundige uitleg van Doron die alles weet van de historische en geografische ontwikkelingen van deze voor zowel het Jodendom als de Islam zeer belangrijke plek. Het bezoek werd afgesloten door een heerlijke koffie met chumus-ontbijt in “katoenmarkt”, een straatje in de Oude Stad. De PThU heeft sinds 2017 een Erasmus+ overeenkomst met het Schechter Instituut waarbij zowel studenten als studenten van beide instellingen een tijd aan het partnerinstituut kunnen doceren c/q studeren. Het Schechterinstituut is een Joodse tegenhanger van de PThU, een relatief kleine academische instelling waar zowel geïnteresseerde leken als rabbijnen in opleiding theologisch onderwijs volgen. In de vorige periode hebben vier studenten van de PThU en een aantal medewerkers van beide instellingen van de uitwisseling gebruik gemaakt . Voor studenten bedraagt de studietermijn minstens drie maanden. Een cursus modern Hebreeuws is inbegrepen. Docenten gaan voor minstens vijf dagen waarin ze acht uur college geven.

Erasmus+ verblijf Schechter docenten aan de PThU

In de week van 16 mei waren dr. Tamar Kadari en dr. Ari Ackerman, docenten aan het Schechter Instituut in Jeruzalem, te gast aan de PThU in het kader van onze Erasmus+ samenwerking. Beide Israëlische docenten hebben een college gegeven in de joint-BA cursus “Onopgeefbaar Verbonden”. Kadari gaf op maandag een geanimeerde les over de rabbijnse interpretatie van het Hooglied, waarin soms een anti-Christelijke ondertoon te vinden is. In de Christelijke lezing van dit mooie bijbelboek vindt men daarentegen vaak anti-Joodse elementen. De studenten waren zeer coöperatief en deelden ook hun ervaringen met het Hooglied in de kerk, wat in de meeste gevallen niet veel was. Een student verwees echter naar het populaire lied “You won’t relent” gebaseerd op het Hooglied, dat in zijn kerk gezongen wordt. Een video werd opgezocht en getoond.

Op donderdag verraste Ari Ackerman ons met een zeer helder college over de (positieve) houding van Abraham Joshua Heschel tegenover het Christendom en andere religies. Hij deed dit aan de hand van Heschel’s artikel “No Religion is an Island” , een bekende foto van Heschel met Martin Luther King tijdens de mars in Selma, en een interview afgenomen een aantal weken voor Heschel’s dood.

Op dinsdag hebben beide docenten een hele dag meegedraaid in een PhD seminar over het boek Ester. PhD kandidaten Esther van Eenennaam en Benjamin Bogerd hebben eerst een onderdeel van hun beginnende onderzoek gepresenteerd, over respectievelijk Joodse houdingen tegenover digitale media in de liturgie, waaronder het lezen van de Esther-rol (Esther van E., en de Targum Sheni, een Aramese interpreterende vertaling van het boek Esther (Benjamin B.). Daarop gaven Ackerman en Kadari feedback en hebben zij elk nog een eigen lezing gehouden. De opkomst van studenten en docenten was teleurstellend, maar daar hebben de gasten zich niet door laten storen: de aanwezigen hebben een bijzonder leerrijke dag gehad met intensieve uitwisseling van gedachten.

Deze uitwisseling volgde op de deelname van beide Schechter docenten aan de conferentie van het Jewish en Christian Perspectives consortium (zie hier de aftermovie door Kevin Smits). Daar gaf de president van Schechter Instituut, professor Doron Bar, de openingslezing. In de week van 23-27 mei is Lieve Teugels te gast bij het Schechter Instituut voor een tegenbezoek. Verslag daarvan volgt.

New: Filmed Classes for the course “The Adventures of Lady Wisdom”

With Halyna Teslyuk of Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv, Ukraine, I am developing a course on the Jewish and Christian reception history of personified Wisdom as presented in the biblical book Proverbs. The course focuses on texts and images, among which Orthodox icons. Halyna and I are currently teaching the course simultaneously at UCU and PThU in Amsterdam as a hybrid course. Here are the links to some of the video’s produced by filmmaker Rob Nelisse of Imageworkplace and myself.

- Rabbinic Wisdom Part 1 (Teugels) https://vimeo.com/625850869/9197dfd00c

- Rabbinic Wisdom Part 2: https://vimeo.com/627270886/3f55b26b23 (Teugels)

- Rabbinic Wisdom Part 3 (Teugels) https://vimeo.com/627288571/1cf3dd9f3f

- Rabbinic Wisdom Part 4 (Teugels) https://vimeo.com/627298677/00cb7b2051

- Rabbinic Wisdom Part 5 (Teugels) https://vimeo.com/627316653/c82f64845f

- Icons: Novogrod type Sophia (Teugels & Van Es) https://vimeo.com/509759087

- Icons: Kyiv type Sophia https://vimeo.com/506603301 (Teugels & Van Es)

- Icons: David Chichua Paints a Sophia Icon https://vimeo.com/510450226/b0b4b46eed (Teugels& Chichua)

- Sophia in Protestant Mysticism (Kick Bras) https://vimeo.com/562112138

- Sophia in Thomas Merton (Kick Bras) https://vimeo.com/562105884

Sjana tova! Een blog over, onder andere, de maan in Psalm 81:4

voor de originele publicatie zie https://www.pthu.nl/bijbelblog/2021/09/nieuwe-maan-of-volle-maan/

Rosj haSjana

In de NBV luidt Psalm 81:4 als volgt:

Blaas (tik’u) op de ramshoorn (sjofar) bij nieuwemaan (chodesj)

En bij vollemaan (keseh) voor onze feestdag

Ik heb in bovenstaand vers een paar woorden uit het Hebreeuwse origineel toegevoegd, omdat deze relevant zijn voor dit verhaal. Ik zou “vollemaan” anders willen vertalen. Daarover straks meer.

Ik wil het nu eerst namelijk hebben over Rosj haSjana, de eerste dag van het Joodse Nieuwe Jaar. Alle Joodse maanden, zo ook Tisjrei, beginnen met de nieuwe maan. Het Jodendom kent immers een maankalender. Elke nieuwe maan is een feestdag, maar de eerste van Tisjrei is een bijzondere feestdag omdat op deze dag niet alleen een nieuwe maand, maar ook een nieuw jaar begint. De periode voorafgaand aan Rosj haSjana kenmerkt zich door inkeer en bezinning. Men kijkt terug op wat in het vorige jaar goed ging en wat beter kon, en bereidt zich voor op het komende jaar. De tien dagen tussen Rosj haSjana en Jom Kippoer bieden een laatste kans, een soort blessuretijd, om dit alsnog te doen.

Sjofar

De sjofar, de ramshoorn, vertolkt de urgente roep tot inkeer. Vanaf de maand voorafgaand aan Rosj haSjana tot en met Jom Kippoer, wordt deze herhaaldelijk geblazen. Met Rosj haSjana en Jom Kippoer gebeurt dit in de synagoge, aan de hand van een vastgelegd patroon van herhaalde tonen op de sjofar, variërend tussen kort en lang, vloeiend en stotend, en culminerend in een heel lange aangehouden toon. Deze laatste wordt tekia gedola – grote sjofartoon, genoemd. U ziet wellicht het verband tussen tik’u in Ps 81:4 en het woord tekia. Het gaat hier inderdaad om dezelfde stam die gebruikt wordt om het blazen op de sjofar weer te geven. Ook de sjofar komt immers voor in dat vers.

“Tussen de nieuwe maan en de tiende”

De periode tussen Rosj haSjana en Jom Kippoer wordt in het Jodendom aangeduid met bein keseh le’ asor – tussen de nieuwe maan en de tiende. Keseh betekent in deze uitdrukking “nieuwe maan”. Het is afgeleid van het werkwoord dat “bedekken” betekent, ksh: de bedekte maan dus. Op de tiende van de maand Tisjrei valt, zoals gezegd, Jom Kippoer. In de Joodse traditie, en in de bijbelwetenschap, worden een aantal Psalmen, met name deze waar het koningschap van God centraal staat, verbonden met Rosj haSjana. Zo ook Psalm 81. Laten we even terugkeren naar Ps 81:4. In de eerste helft van het vers is het verband met Rosj haSjana duidelijk:

Blaas (tik’u) op de ramshoorn (sjofar) bij nieuwemaan (chodesj)

Chodesj betekent in feite “maand” – het gaat dus om het begin van de maand. Echter, in de tweede vershelft is, volgens de NBV, de meeste bijbelvertalingen, en vrijwel alle woordenboek voor Bijbels Hebreeuws, sprake van “vollemaan”.

En bij vollemaan (keseh) voor onze feestdag

“Vollemaan” is de vertaling van keseh. Hoezo? Keseh betekende toch nieuwe maan in de uitdrukking bein keseh le’asor – tussen de nieuwe maan en de tiende? Hoe komen de vertalers erop dat keseh, de bedekte maan, volle maan zou betekenen?

‘Traditonele’ vs ‘niet traditionele’ commentatoren

Ik vond antwoorden op deze intrigerende vraag in een uitgave van Johannes de Moor [Johannes C. de Moor, New year with Canaanites and Israelites. 2 delen. Kamper Cahiers 21-22 (Kampen: Kok, 1972)], en in een van Solomon Freehof [Solomon B. Freehof, “Sound the Shofar: “Ba-Kesse” Pslam 81:4, in The Jewish Quarterly Review 64 (1974) 225-228.]

Beide studies ondersteunen mijn overtuiging dat in Ps 81:4, in beide vershelften, de nieuwe maan bedoeld is, en niet de volle maan. Freehof maakt onderscheid tussen “traditionele” versus “niet traditionele” commentatoren. Met de eerste bedoelt hij de Joodse bronnen, Rabbijnse teksten en Joodse bijbelgeleerden uit de middeleeuwen en later, en met de laatste bedoelt hij de, veelal christelijke, moderne bijbelwetenschappers, zoals Wellhausen, Duhm, en Briggs, die hij noemt. De Joodse bronnen, en ook moderne Hebreeuwse woordenboeken, zoals Even Sjosjan, vertalen keseh unaniem als “nieuwe maan”, gebaseerd op het evidente verband tussen keseh en de stam ksh, bedekken. De meeste academische exegeten en bijbelvertalers lezen echter “volle maan”.

Een argument voor volle maan zou zijn dat “onze feestdag” alleen op een groot feest kan slaan dat op volle maan valt, zoals het Loofhuttenfeest of Joodse Paasfeest. Verder halen zij parallellen aan uit het Akkadisch waar een gelijkaardige stam kuse’u zou slaan op de “haartooi van de maangod ten tijde van de volle maan” (zo ook in het woordenboek HALOT). In de Bijbel (alsook in de Joodse traditie) zijn er bovendien meerdere “nieuwjaren” en er zijn ook verbanden met nieuwjaarsfeesten uit het Oude Nabije Oosten. Hierop ingaan zou ons veel te ver leiden, maar u kan er De Moor op nalezen. Er zijn dus nog andere argumenten om in de eerste vershelft “nieuwe” en in de tweede “volle” maan te lezen. Voor mij zijn deze echter niet overtuigend.

Poëtisch parallelisme

Zoals in vele verzen in de Psalmen vinden we in dit vers immer een poëtisch parallelisme. Dat wil zeggen dat in de twee vershelften hetzelfde wordt gezegd met andere woorden. Dit is een zeer bekend fenomeen, met name bij moderne bijbelwetenschappers. Bovendien zien we hier een chiastische constructie, wat wil zeggen een a-b-b-a constructie: chodesj en keseh staan op de positie van de twee b’s. Men verwacht dat deze woorden synoniemen zijn. Dit, in combinatie met de evidente betekenis van de stam ksh, die bedekken betekent, en de lange Joodse traditie die dit woord altijd als een verwijzing naar de nieuwe maan heeft gezien, pleit voor een vertaling van “nieuwe maan” in beide vershelften van Ps 81:4. Waarom beroep doen op de hoofdtooi van een Akkadische maangod, bovendien met een iets andere spelling (ks’), als er een evidente, logische vertaling bestaat met een lange traditie, die bovendien recht doet aan het poëtisch parallelisme van het vers?

Dit is slechts een voorbeeld van hoe een deel van de academische studie van het OT en het Hebreeuws vaak zeer ver verwijderd is van de Joodse (uitleg)traditie, waar deze teksten ononderbroken voor minstens 2000 jaar bestudeerd zijn geweest, waar ze altijd gebruikt zijn, in de liturgie, en in uitdrukkingen zoals bein kese le’aser. Meer bekendheid met deze traditie, ook bij bijbelvertalers, zou soms tot alternatieve inzichten kunnen leiden, zodat niet klakkeloos wordt overgenomen wat in eerdere vertalingen, woordenboeken en commentaren staat. Ik ben benieuwd hoe dit vers in de NBV21 zal luiden.

Een nieuwe bijbelblog van mijn hand over de adelaars en de twijgjes in Ezechiel 17

Interviews in het ND

Op 27 maart 2021 verschenen twee interviews met mij in het Nederlands Dagblad, in de zaterdag- en zondagbijlage. In deze bijdragen worden mensen gevolgd in hun activiteiten op deze twee dagen. De interviews zijn vergezeld van foto’s van Rob Nelisse. Klik op de links hieronder.

‘In Amerika heb ik de stap gezet om joods te worden’ _ Nederlands Dagblad

‘Dat hardlopen werd steeds serieuzer’ _ Nederlands Dagblad

Elia en Pesach: PThU Bijbelblog 1 april 2021

Pesach

Het Pesachfeest kent een aantal bijzondere gebruiken. Zo vermijdt men gerezen deeg gedurende acht dagen en gebruikt men deeg zonder gist voor platte harde matzes. Op de eerste avond van Pesach wordt de traditionele sedermaaltijd gegeten. Dat is een maaltijd waarbij symbolische spijzen worden gegeten, en de uittocht uit Egypte wordt naverteld en bezongen. In het ”handboek” daarvoor, de Haggada, wordt het hele ritueel van de maaltijd stap voor stap beschreven.

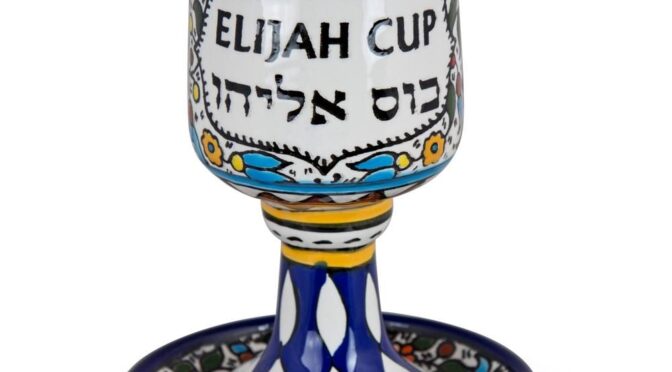

Een bijzonder aspect van de sederavond is de rol van de profeet Elia, ook Elijahoe genoemd. Deze is op twee manieren aanwezig – of eigenlijk juist niet aanwezig: op een bepaald moment wordt de deur voor hem opengezet en bovendien wordt er een glas wijn voor hem ingeschonken, de zogenaamde “beker van Elia.” Dit glas wordt niet door een van de gasten leeg gedronken: het staat er voor het geval Elia die avond op bezoek zou komen.

Vier of vijf glazen wijn?

In de rabbijnse traditie legt men de beker van Elia zo uit: Ooit was er een meningsverschil over het aantal glazen dat men per persoon tijdens de seder moet drinken, vier of vijf. Het aantal glazen wordt in verband gebracht met de werkwoorden van bevrijding die in Exodus 6:6-8 worden gebruikt:

“Ik ben de HEER. Ik zal de last die de Egyptenaren jullie opleggen van je afnemen, ik zal jullie uit je slavenbestaan bevrijden. Met opgeheven arm zal ik jullie verlossen en de Egyptenaren zwaar straffen. Ik zal jullie aannemen als mijn volk, en ik zal jullie God zijn. En jullie zullen inzien dat ik, de HEER, jullie God ben, die jullie bevrijdt van de last die je door de Egyptenaren is opgelegd. Ik zal jullie naar het land brengen dat ik onder ede aan Abraham, Isaak en Jakob beloofd heb; dat land zal ik jullie in bezit geven. Ik ben de HEER.”

De laatste vorm van bevrijding “ik zal jullie naar het land brengen,” (vers 8) had tijdens het vieren van het eerste Pesach in de woestijn nog niet plaatsgevonden. Daarom liet men de vijfde beker over voor de komst van Elia. Hoezo voor Elia?

Elia en de messias

Ook vandaag nog staat de beker van Elia voor toekomstige bevrijding. Een bezoek van Elia tijdens de seder zou wel heel bijzonder zijn, want het zou het begin van de messiaanse tijd betekenen. Op het moment dat het glas wordt gevuld en de deur wordt opengezet, lezen we in de Haggada een citaat uit het bijbelboek Maleachi:

Voordat de dag van de Eeuwige aanbreekt, die groot is en ontzagwekkend, stuur ik jullie de profeet Elia, en hij zal ervoor zorgen dat ouders zich verzoenen met hun kinderen en kinderen zich verzoenen met hun ouders. Anders zou ik het land volledig moeten vernietigen.(Bron: Maleachi 3:23-24)

Deze tekst is de bijbelse oorsrong van de gedachte dat Elia zal komen “voor de dag van de Eeuwige aanbreekt.” Elia wordt op grond van deze tekst dus gezien als de voorloper van de messias.

In de Haggada volgt hierop een lied over Elia:

Eliyahu hanavi Eliyahu hatishbi, Eliyahu hagil’adi – Bim’hera, beyamenu, yavoh eleinu, im mashiach ben David.

Elijahoe de profeet, Elijahoe de Tisbiet, Elijahoe de man uit Gilead, dat hij spoedig, in onze dagen, zal komen naar ons met de messias, de zoon van David.

Dat Elia een Tisjbiet was uit Gilead weten we uit 1 Koningen 17:1, waar Elia voor het eerst in de Bijbel op het toneel komt, als een profeet ten tijde van koning Achab. De profeet Elia heeft reeds in het Bijbelse verhaal bijzondere gaven: zo verricht hij wonderen met voedsel (1 Kon 17:16) en is hij in staat een dood kind weer levend te maken (1 Kon 17:22). Ook het einde van Elia is merkwaardig: hij sterft niet, maar wordt “opgenomen” door God, in een wagen met paarden van vuur. (2 Koningen 2:2-11) Omdat Elia niet gestorven is, gaat men ervan uit dat hij kan terugkomen. In de tekst uit Maleachi komt die gedachte al naar voren. In de latere Joodse traditie wordt die terugkomst verbonden met de komst van de messias.

De hymne “Eliyahu hanavi” wordt niet alleen tijdens de seder gezongen maar ook elke zaterdagavond bij het einde van de sjabbat, op het moment dat de overgang naar de nieuwe week markeert. De betekenis is hier dat men bidt dat Elia “spoedig, in onze dagen” – namelijk in de volgende week – zal komen als voorloper of begeleider van de messias.

Wachten Joden op de messias?

Hoewel Joden elke week het verlangen naar de komst van de messias en zijn voorloper Elia uitspreken, hebben de meesten geen dringende verwachting van die tijd. Het is eerder een verwachting van een eindtijd waarin alles goed zal zijn. In elke generatie vult men die verwachting op een andere manier in. Vandaag de dag, onder de bedreiging van een epidemie, wordt deze gekleurd door het groeiende besef dat we de aarde zullen uitputten als we niet snel en efficiënt ingrijpen. Ook door de nog steeds grote ongelijkheid tussen mensen, op wereldschaal en in eigen land, krijgt de messiaanse tijd een eigentijdse invulling. Aan het einde van de Pesachseder wenst iedereen elkaar “volgend jaar in Jeruzalem” toe.

Daarover schreef rabbijn David :

De beker is ingeschonken, maar nog niet gedronken. Toch wordt de beker van hoop elk jaar ingeschonken. Pesach is de nacht voor roekeloze dromen; voor visioenen over wat een mens kan zijn, wat de samenleving kan zijn, wat mensen kunnen zijn, wat geschiedenis kan worden. Dat is de betekenis van “volgend jaar in Jeruzalem.”

Pasen

Niet toevallig vieren christenen in deze tijd Pasen. Dat heeft alles te maken met de Jood Jezus die een dag voor zijn dood Pesach vierde met zijn leerlingen, en vervolgens opstond uit de dood. Het woord Pasen is, via het Aramese Pascha, rechtstreeks afgeleid van Pesach. Jezus wordt door christenen als de messias beschouwd. Johannes de Doper wordt daarbij gezien als Elia, zoals blijkt uit de citaten uit Maleachi en de verwijzingen naar Elia in de Evangeliën (bijv. Lucas 1:17; Marcus 9:4-5; Matteüs 17:3-4; Lucas 9:30-33). In de Orthodoxe traditie wordt Johannes zelfs “de Voorloper” genoemd. Toch verwachten ook christenen een terugkomst van de messias. De verwachting van de toekomstige messiaanse tijd is niet heel anders dan bij de joden. Rabbijn Hartmans beschrijving van Pesach als een feest van “roekeloze dromen; (…) visioenen over wat een mens kan zijn, wat de samenleving kan zijn, wat mensen kunnen zijn, wat geschiedenis kan worden” zal ook door vele christenen gedeeld worden als een invulling van de ultieme betekenis van Pasen.

Online cursus over Sophia

Samen met Halyna Teslyuk uit Lviv ontwerp ik een cursus over de interpretatie en de ontwikkeling van de figuur van “vrouwe Wijsheid” (Chokhma, Sophia) in Jodendom en Christendom voor studenten van de Protestantse Theologische Universiteit (PThU) en Ukrainian Catholic University, en andere belangstellenden. Kick had als filmset de prachtige oude kerk in Spaarndam uitgezocht: we hebben alle hoeken van het gebouw benut voor het filmen van Kick’s boeiende lessen over de betekenis van Sophia voor protestantse mystici en Thomas Merton. Alles is op film gezet door Rob Nelisse. Volgende reeks video’s: Wijsheid in de rabbijnse literatuur door ondergetekende. Zie ook http://lieveteugels.nl/?p=504